Pune: India technology policy reflects a complex mix of regulatory clarity and inconsistency, particularly in emerging areas such as artificial intelligence, intermediary governance, and digital assets, according to Sunil Abraham, Public Policy Director – Data Economy & Emerging Tech, Meta India.

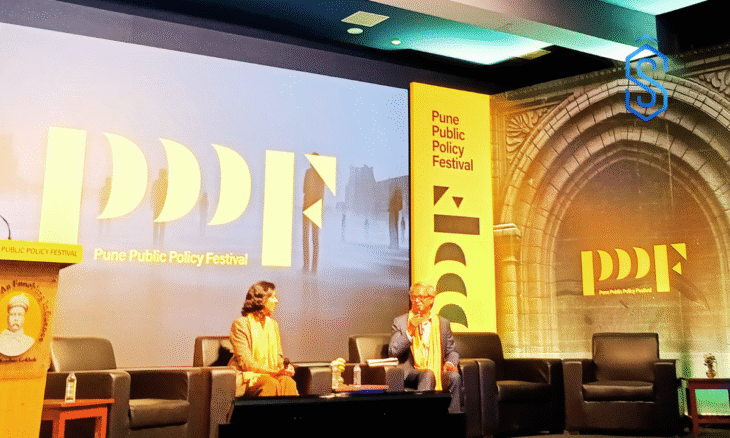

Speaking during a fireside chat at the Pune Public Policy Festival – PPPF 2026, Abraham offered a detailed assessment of India’s evolving policy posture in conversation with moderator Saranya Gopinath, Head of Government Affairs & Public Policy at Razorpay.

India Technology Policy Shows Extremes in Regulatory Thinking

Addressing the current state of India technology policy, Abraham said it is difficult to view government action through a single, coherent framework. Instead, he described policymaking as oscillating between highly thoughtful interventions and poorly designed regulations, often emerging from the same ministry within a short span of time.

He cited amendments to the Section 79 (IT Act) video takedown process as an example of strong policymaking, highlighting safeguards such as senior-level authorization, reasoned orders, and adherence to the principles of necessity and proportionality.

In contrast, he pointed to the “synthetically generated information” rules as an example of regulatory inconsistency, arguing that they lacked technological feasibility and policy coherence.

Balancing Stakeholder Interests in India Technology Policy

Abraham emphasized that India technology policy is fundamentally about balancing competing stakeholder interests. He identified five key stakeholders in AI governance: intellectual property producers, IP owners, paying users, non-paying users, and the government.

According to him, effective policy is achieved when no single group is disproportionately satisfied, a principle he referred to as “policy dharma.”

Drawing parallels with platform governance, Abraham noted that sustained trust in regulation emerges when policymakers avoid rigid positions and instead focus on proportional, balanced outcomes.

He warned that excessive reliance on prohibition – outside narrow contexts – often reflects policy failure rather than strength.

Also Read: AI-Driven Loan Processing Enables 25,000 Monthly Loan Closures at Bajaj Finserv

Artificial Intelligence Challenges Traditional Regulatory Frameworks

Turning to artificial intelligence, Abraham said AI represents an omnibus policy domain where multiple strands – innovation, rights, governance, and cultural policy – intersect simultaneously.

Unlike cryptocurrency or intermediary guidelines, AI disrupts traditional regulatory assumptions and complicates the identification of core governmental interests.

He observed that under frameworks such as the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, the Indian government has articulated a balancing approach that protects users while enabling innovation.

He cautioned against abandoning this model in AI regulation, arguing that overly prescriptive approaches could drive companies and research activity to other jurisdictions.

India Technology Policy in the Global AI Landscape

Placing India technology policy in a global context, Abraham contrasted the European Union’s regulation-first approach with the United States’ innovation-led stance.

He noted that India is pursuing a distinct path – investing in AI infrastructure such as GPU clusters and indigenous models while resisting premature regulatory intervention.

He highlighted the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology’s (MeitY) view that there is no regulatory vacuum in AI, asserting that existing laws continue to apply even when AI systems are involved.

This regulatory conservatism, he said, explains why some recent AI-related rules came as a surprise to the policy community.

India Technology Policy: Questioning the Notion of Sovereign and Indigenous AI

Abraham challenged assumptions around sovereign or indigenous AI models, arguing that restricting global models from training on Indian data is both impractical and counterproductive.

He cited publicly funded research institutions such as CSIR, where open-access publication is mandated, questioning the logic of preventing such knowledge from being embedded in global AI systems.

According to him, India technology policy should prioritise human capability over model nationalism. He argued that true sovereignty lies in producing skilled researchers, engineers, and mathematicians capable of building and training advanced systems, rather than focusing narrowly on the origin of specific AI models.

Also Read: PM Narendra Modi Engages with Indian AI Start-Ups Ahead of India AI Impact Summit 2026

Bias, Responsibility and the Limits of “Responsible AI”

On the issue of bias, Abraham referenced Indian academic research benchmarking bias across caste, religion, and community, calling it among the most comprehensive work globally. He cautioned against treating bias as a purely national issue, noting that calibration often depends on context and use case.

He also raised concerns about narrowly defined “responsible AI,” warning that excessive constraints could undermine AI’s usefulness as a general-purpose technology.

Drawing analogies with tools such as electricity, automobiles, and knives, he argued that AI’s dual-use nature cannot be eliminated through regulation alone.

Liability, Capacity Building and Regulatory Conservatism

Discussing liability frameworks, Abraham said responsibility should rest with those who deploy AI systems within regulated contexts rather than with open-source model providers.

He compared this to the Linux ecosystem, where liability lies with product manufacturers rather than the underlying open-source software.

In closing, Abraham advocated a regulatory conservative approach, where minimal regulation is complemented by strong capacity building through education and research funding.

He argued that familiarity with technology reduces fear over time and that policy should focus on building resilience rather than enforcing broad prohibitions.